Bolanle Elizabeth Arokoyo

Morphology Lecture Series XI

We will conclude our discussion of Derivational Morphemes by looking at adjective and adverb derivations today. The last topic discussed was Verb Derivation. Endeavour to read the previous topics.

1. Adjective Derivation

Adjective is a lexical category that serves to qualify noun. It occurs as a modifier in noun phrases.

Adjectives can be derived from nouns, verbs and also from adjectives giving rise to denominal adjectives, deverbal adjectives and deadjectival adjectives.

1.1 Denominal Adjectives

Denominal adjectives are derived from nouns.

Relational adjectives (adjectives with a relation to the base noun and derived from noun), privative adjectives (adjectives derived from nouns indicating lack of possession of a noun), material adjectives (adjectives indicating materials used in creation), possession adjectives (adjectives indicating ownership), resemblance adjectives (adjectives indicating similarities), proprietive adjectives (adjectives indicating possession of the base noun), etc. are some adjective types that can be derived from nouns. In

English for example, the suffixes –ful, –an, -ly, -ish etc. are added to noun bases to derive proprietive adjectives.

1. Noun Adjective

a. beauty beauty-ful

b. hand hand-ful

c. Nigeria Nigeri-an

d. America Americ-an

e. man man-ly

f. coward coward-ly

g. boy boy-ish

h. girl girl-ish

In Tagalog, tones serve as the affix to derive also proprietive adjectives from nouns. Consider the following examples taken from Haspelmath and Sims (2010, p. 56).

2. Noun Adjective

a. búhay ‘life’ buháy ‘alive’

b. gútom ‘hunger’ gutóm ‘hungry’

c. tákot ‘fear’ takót ‘afraid’

d. hábaɁ ‘length’ habáʔ ‘long’

e. gálit ‘anger’ galít ‘angry’

To derive adjectives in the language, the high tone on the vowel in the first syllable is elided and the vowel in the second syllable receives the high tone.

The suffix –less in English derives privative adjectives. Consider the following examples in (3).

3. Noun Adjective

a. pepper pepper-less

b. water water-less

c. colour colour-less

d. paper paper-less

English derives material adjectives with the addition of suffixes –en, -ic, etc. to specific nouns.

4. Noun Adjective

a. wood wood-en

b. wool wooll-en

c. gold gold-en

d. metal metall-ic

English also derives adjectives with the meaning of covering with the suffix –y as shown in the following examples.

5. Noun Adjective

a. velvet velvet-y

b. wool wooll-y

c. wood wood-y

d. stone ston-y

Modern Arabic uses the nisba suffix i.e. relational suffix to derive material, possession and resemblance adjectives.

These three adjectival kinds express relations. Let us consider the following examples taken from Druel and Grandlaunay (2008, p.379).

6. Noun Adjective

a. ʤibs ‘plaster’ ʤibs-i: ‘made of plaster’

b. ħadi:d ‘iron’ ħadi:d-i: ‘made of iron’

c. blastik ‘plastic’ blastik-i: ‘made of plastic’

7. Noun Adjective

a. ʤabal ‘moutain’ ʤabal-i: ‘mountanous’

b. ʃaʼr ‘hair’ ʃaʼr-a:n-i: ‘hairy’

c. duhn ‘grease’ duhn-i: ‘greasy’

8. Noun Adjective

a. tibn ‘straw’ tibn-i: ‘straw coloured’

b. muxmal ‘velvet’ muxmal-i: ‘velvety’

c. ˀisfi:n ‘wedge’ ˀisfi:n-i: ‘wedge shaped’

From the examples above indicating the derivation of material adjectives in (6) possession adjectives in (7) and resemblance adjectives in (8) from nouns, since they all have the same suffix, the resultant adjective is determined by the type of noun the denominal suffix -i is attached to.

Relational adjectives express the relation between it and the head noun. Let us see the following examples in (9).

9. Noun Adjective

a. government government-al

b. element element-al

c. judgment judgment-al

d. medicine medicin-al

e. industry industry-al

f. relation relation-al

In English, denominal relational adjectives could be derived with the suffix –al as indicated in the examples above.

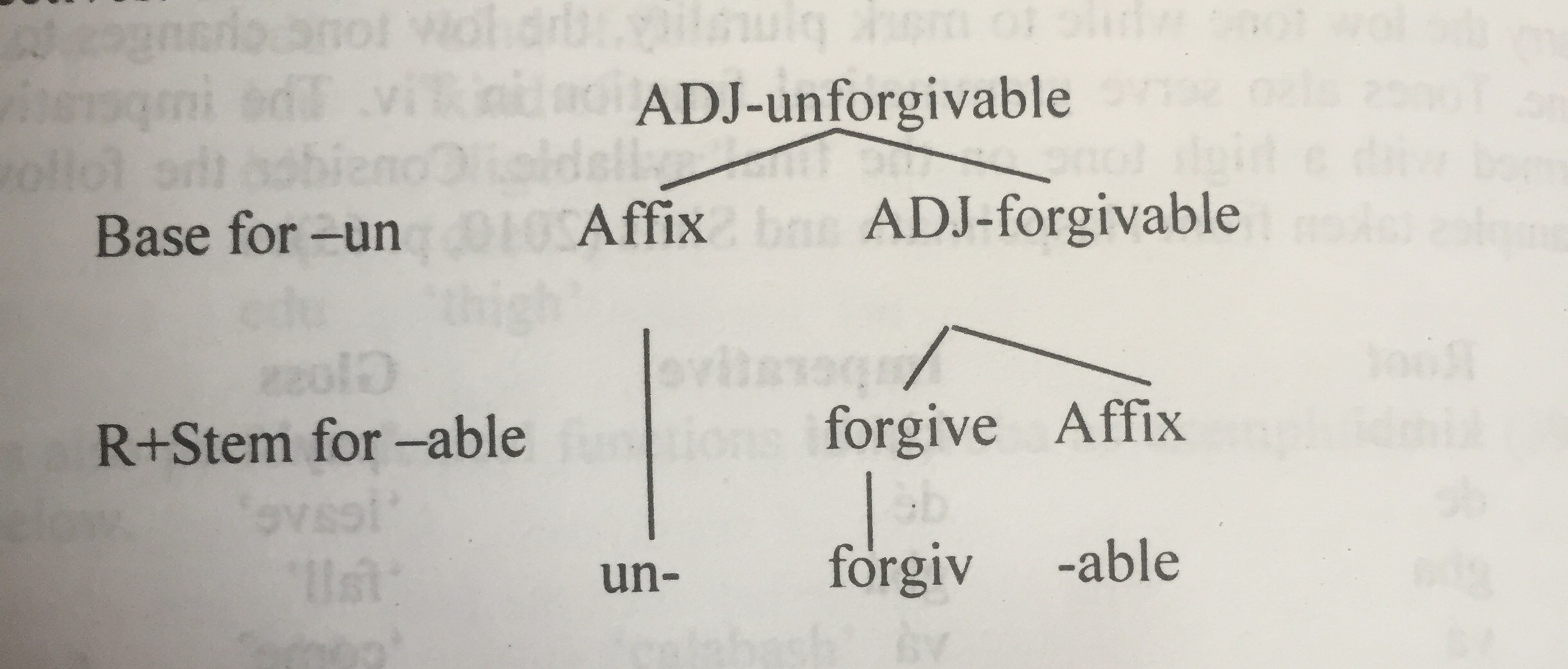

1.2. Deverbal Adjectives

Deverbal adjectives are adjectives derived from verbs.

Facilitative (an adjective meaning ‘able to undergo an action’) and agentive (an adjective indicating an action performed by the noun) adjectives are some of the kinds of adjectives derived from verbs. Consider the following examples.

10. Verb Adjective

a. read read-able

b. like like-able

c. carry carry-able

d. manage manage-able

The suffix –ive is attached to the following verbs to derive adjectives.

11. Verb Adjective

a. attract attract-ive

b. elude elus-ive

c. suggest suggest-ive

d. prohibit prohibit-ive

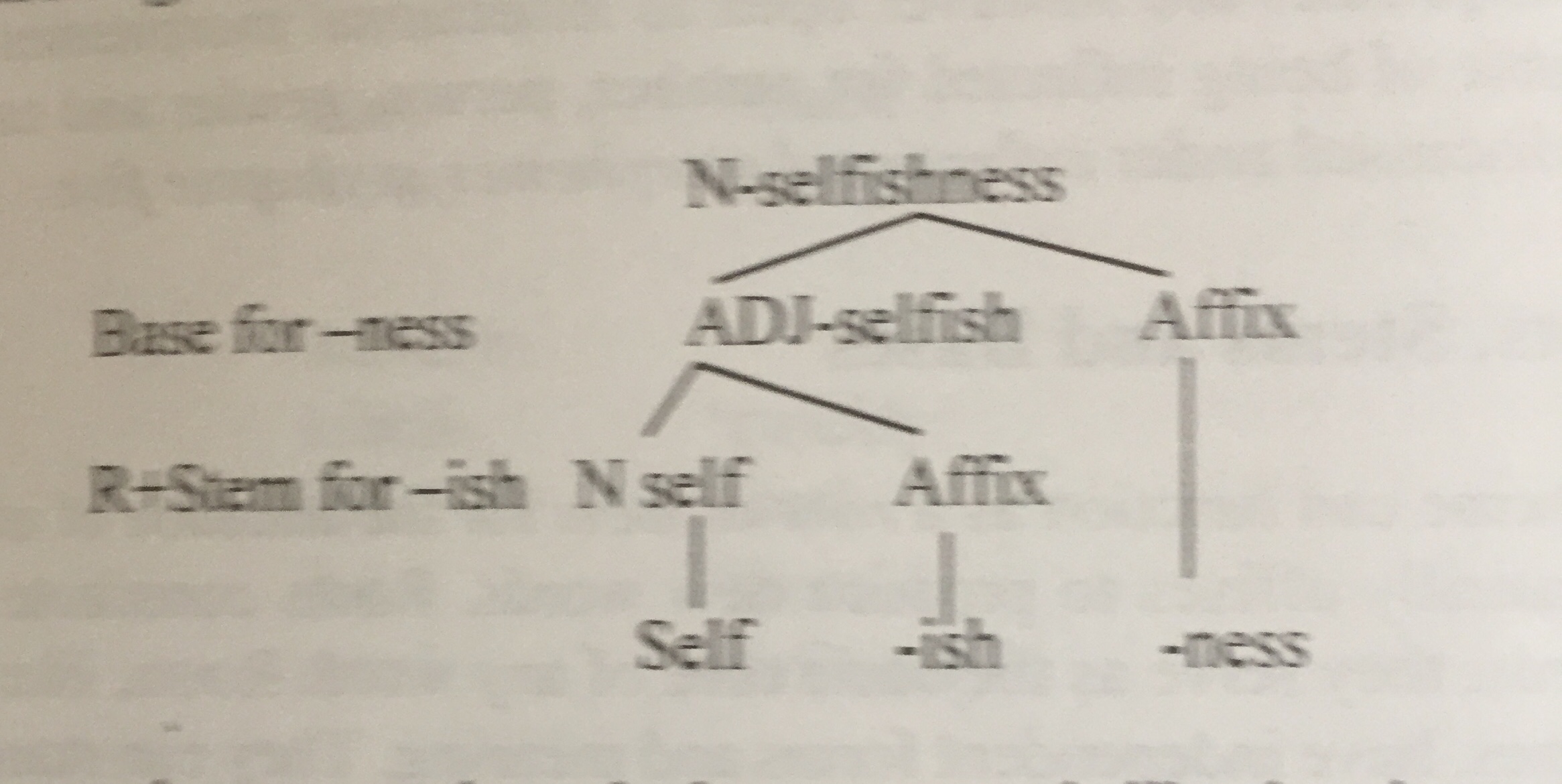

1.3. Deadjectival Adjectives

Deadjectival adjectives are adjectives derived from other adjectives.

The kinds of adjectives derived from others include negative adjective (an adjective indicating a reversal of the values of the base adjective), attenuative adjective (an adjective that indicates a reduced degree of the base adjective), intensive adjective (an adjective indicating an increased degree of the base adjective), etc.

German uses the prefix un- to derive negative adjectives from other adjectives.

12. Adjective Adjective

a. schön ‘beautiful’ un-schön ‘ugly’

b. glücklich ‘happy’ unglücklich ‘unhappy’

c. bestimmte ‘countable unbestimmte ‘uncountable’

The affixes un-, il-, in-, etc. are attached to adjectives to derive negative adjectives in English. For example:

13. Adjective Adjective

a. happy un-happy

b. approachable un-approachable

c. logical il-logical

d. legal il-legal

e. eligible in-eligible

f. competent in-competent

The suffix –ish derives attenuative adjectives in English as indicated in the examples in (14).

14. Adjective Adjective

a. red red-ish

b. pink pink-ish

c. green green-ish

d. white whit-ish

Tzutujil also derives attenuatives using the duplifix –Coj. Consider the following examples taken from Dayley (1985, p213).

15. Adjective Adjective

a. saq ‘white’ saq-soj ‘whitish’

b. rax ‘green’ rax-roj ‘greenish’

c. q’eq ‘black’ q’eq-q’oj ‘blackish’

d. tz’iil ‘dirty’ tz’il-tz’oj ‘dirtyish’

In deriving intensive adjectives, there is the partial reduplication of the initial syllable with the addition of an interfix in Turkish. Consider (16).

16. Adjective Adjective

a. kirmizi ‘red’ kip-kirmizi ‘all red’

b. kolay ‘easy’ kop-kolay ‘extremely easy’

c. beyaz ‘white’ bem-beyaz ‘all white’

d. temiz ‘clean’ ter-temiz ‘completely clean’

In the derivation of some of these adjectives as indicated in the Tzutujil and Turkish examples, we see that partial reduplication is used.

2. Adverb Derivation

An adverb is a lexical category that modifies the verb and the adjective.

Adverbs could be derived from verbs, adjectives and nouns through the process of affixation.

Adjectives easily receive affixes to derive adverbs in English. For example:

17. Adjective Adverb

a. high high-ly

b. easy easi-ly

c. foolish foolish-ly

d. beautiful beautiful-ly

The addition of the prefix a- to adjectives verbs and nouns also derive adverbs. For example:

18. Adjective Adverb

a. long a-long

b. far a-far

c. lone a-lone

d. loud a-loud

19. Verb Adverb

a. stray a-stray

b. drift a-drift

c. board a-board

d. miss a-miss

20. Noun Adverb

a. head a-head

b. pace a-pace

c. breast a-breast

d. back a-back

Examples (18) show adverbs derived from adjectives, (19) indicate adverbs derived from verbs while (20) exemplify adverbs derived from nouns.

Combining the suffix –wise and –ward to some kinds of nouns in English derives adverbs as exemplified in (21).

21. Noun Adverb

a. clock clock-wise

b. street street-wise

c. east east-ward

d. north northward

The suffix –wise indicates behavior while suffix –ward indicates direction.

Adverbs are also derived from other adverbs. For example, the prefix anti- added to the adverb clockwise will derive anti-clockwise, also an adverb.

Exercises

1. Describe how adjectives are derived.

2. Discuss the derivational functions of affixes.

3. Consider the following data from Kannada. Determine the meaning of the suffixes.

khacita ‘certain’ khacitate ‘certainty’

bhadra ‘safe’ bhadrate ‘safety’

ghana ‘weighty’ ghanate ‘dignity’

(Sridhar 1990, p270, 278)

4. With ample illustrations, describe how adverbs are derived.

NB

a. We will start our discussion of Inflectional Morphology from the next lecture.

b Excerpts are taken from Arokoyo (2013, 2017 and 2018).

References

Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth. (2013). Owé linguistics: an introduction. Ilorin: Chridamel Books. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325247296_Owe_Linguistics_an_Introduction

Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth. (2017). Unlocking morphology. Ilorin: Chridamel Publishing House.

Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth. (2018). Owé linguistics: an introduction. Aba: NINLAN

Dayley Jon P. (1985). Tzutujil grammar. Berkeley: University of Carlifornia Press.

Druel, Jean N., Du Grandlaunay René-Vincent. (2008). Nisba. In Versteegh, K. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Vol. III: Lat-Pu. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2008, pp. 377-381.

Haspelmath, Martins and Andrew Sims (2010). Understanding morphology. London: Hodder Education.