Bolanle Elizabeth Arokoyo

Morphology Lecture Series #IV

I hope you understand what we have been doing especially our last lecture on Types of Morpheme. We will continue our lecture by looking at some concepts in morphology. We will be looking at morphs and allomorphs now. We will conclude with roots, stems and bases in the next class.

1. Morphs

A Morph is the phonological or orthographical shape of a morpheme.

A morph is a discrete unit of a morpheme, the actual form in morpheme realization.

Some morphemes could be realized as single morphs for instance free morphemes or simple words like beg, walk, study, etc., while others could be realized as more than one morph depending on their relative position in a construction.

The English past tense morpheme -d in the following words begged, walked and studied is pronounced in three different ways, [-d], [-t] and [-id] as a result of their environments of occurrence.

They are realized as three different morphs. The different realization of morphs is referred to as allomorphs.

2. Allomorphs

Allomorphs are phonologically determined alternant of a morpheme.

They are variants of the same morpheme; an alternate phonetic form of a morpheme.

You have allomorphy when the same bound morpheme, with same meaning, expressing the same idea has different realizations as a result of the conditioning of the environment of occurrence.

The forms that a morpheme is realized are phonologically determined by the environment.

The forms of allomorphs may not be phonemically similar and they always occur in complementary distribution; in mutually exclusive environments. Where a particular variant is found the other cannot be found.

A good example of allomorphy in Yorùbá is the agentive prefix ‘oní’ that takes different forms resulting in [oní ~ alá ~ oló ~ ọlọ́ ~ elé ~ ẹlẹ́] depending on the environment of occurrence. For example:

1.

a. onílé ‘landlord’

b. oníbàtà ‘seller of shoe’

c. aláta ‘pepper seller’

d. elépo ‘oil seller’

e. olómi ‘owner of water’

f. ẹlẹ́ran ‘meat seller’

g. ọlọ́mọ ‘owner of child’

[oní ~ alá ~ oló ~ ọlọ́ ~ elé ~ ẹlẹ́] are allomorphs of the morpheme oní ‘owner of’ or ‘seller of’.

A very important factor in deriving allomorphs is the environment that is phonologically conditioned.

In the examples above, the initial sound of the root morpheme that the bound morpheme is attached to determines the form of the allomorph.

The derivation goes through the process outlined in (2).

2.

a. oní + ilé onílé

owner house ‘landlord’

b. oní + bàtà oníbàtà

owner shoe ‘shoe seller’

c. oní + ata—onáta—oláta—aláta

owner pepper. ‘pepper seller’

d. oní + epo–onépo—olépo–elepo

owner oil ‘oil seller’

e. oní + omi—olómi

owner water. ‘seller of water’

f. oní + ẹja–onẹja—olẹ́ja—ẹlẹ́ja

owner fish ‘fish seller’

g.oní+ọmọ-onọ́mọ—ọlọ́mọ

owner child ‘owner of child’

The morpheme retains its form when it occurs before a root beginning with vowel /i/ and consonants as shown in examples (2a and b) while the form changes and assimilates the initial vowel of the roots in (2c-g).

Before arriving at the final form, a lot of phonological changes have taken place.

There is a single underlying representation oní that is manipulated by phonological rules to arrive at the pronunciation (the various allomorphs) at the surface representation.

The English plural allomorphs make another good example. The form of the plural marker changes depending on the preceding sound. [-s] appears after voiceless non-sibilant sounds (book-s, pot-s, lap-s, cliff-s), [-z] appears after voiced non-sibilant sounds (keg-s, shoe-s, girl-s, bib-s) while [-iz] appears after sibilants (church-es, judg-es, carriage-es).

The different realizations are allomorphic, conditioned by the environment of occurrence.

3. Conditioning of Allomorphy

Conditioning of allomorphy refers to the condition of selecting different allomorphs. It is the environments in which different allomorphs of the same morpheme occurs (Haspelmath and Sims 2010 p323).

There are three kinds of conditioning: phonological conditioning, morphological conditioning and lexical conditioning.

Phonological conditioning affects phonological allomorphs. It is purely phonological environment that determines the choice of variants.

The explanation for the change is strictly phonological and it is predictable from the phonological environment.

For instance, the Yoruba agentive marker data given in (2) is strictly phonologically conditioned.

The English regular past tense allomorphs [-d], [-t] and [-id] are phonologically conditioned. [-d] appears after voiced sounds, begged, showed, bribed, placed, etc. [-t] after voiceless consonants, stopped, packed, hissed, etc. [-id] after alveolar stops- studied, hunted, defeated, etc.

The choice of the English indefinite article is also phonologically conditioned;

an occurs before nouns beginning with vowels – an egg, an apple, an ear, etc

a occurs before nouns with consonant initials like a book, a dog, a table, a bag, etc.

Morphological conditioning means that morphological context determines the choice of allomorph.

It is the particular morpheme and not the pronunciation that determines the choice of allomorph.

This means that unlike phonological conditioning, the choice of allomorph is not predictable.

In some English plurals, knife- knive-z, house-houz-iz, the voiceless fricatives become voiced and therefore receives the allomorph –z.

The forms of these stems are not changed to voiced in other instances for example when they receive the genitive morpheme –‘s; hous’is, knife’s. Let us consider the following data from Futa-Fula, spoken in French Guinea.

3.

a. puttyu ‘horse’

ŋguˀu puttyu ‘this horse’

b. ŋgurndaŋ ‘life’

daˀaŋ ŋgurndaŋ ‘this life’

c. fena.ndɛˀ ‘lie’

dɛˀɛ fena.ndɛ‘ ‘this lie’

d. d’yi.d’yaŋ ‘food’

daˀaŋ d’yi.d’yaŋ ‘this food’

e. gomd’iŋd’oˀ ‘believing’

o. gomd’iŋd’oˀ ‘this believing’

We can see that the choice of the allomorphs for the demonstrative pronoun ŋguˀu~ daˀaŋ~ dɛˀɛ ~ daˀaŋ ~ o ‘this’ is determined by the stem, it is not predictable.

Lexical conditioning occurs where the choice of allomorph is determined by other properties of the base like semantic properties.

The choice of allomorph is unpredictable and is determined by the particular lexeme it attaches to.

Lexical conditioning also accounts for cases where the choice of allomorph cannot be derived from any general rule and has to be learned individually for each word.

An example is the English plural forms. Apart from the regular ones that are marked with the suffix –s, there are some whose plural forms must be learnt on a word-by-word basis.

For example ox-oxen, child-children, sheep-sheep, deer-deer, etc.

The choice of the allomorph is determined by the word and not by any particular rule. Consider the following Hausa phrases.

4.

a. hárcè n‘the tongue’ (masc.)

b. zárè n‘the thread’ (masc.)

c. ídò n‘the eye’ (masc.)

d. kwàndó n‘the basket’ (macs.)

e. úwá r‘the mother’ (fem.)

f. màtá r‘the wife’ (fem.)

g. ùbá n‘the father’ (fem.)

h. rúwá n‘the water’ (fem.)

The particle marking determiner has a gender distinction, r~n. The form is lexically conditioned as it does not have anything to do with the pronunciation or any phonological or morphological rules but rather with the semantic property of the base; the fact that the lexeme it attaches to is either masculine of feminine.

4. Types of Allomorphs

There are basically two types of allomorphs; phonological allomorphs and suppletive allomorphs.

Phonological allomorphs are allomorphs that are similar phonologically. The Yoruba agentive prefix discussed above is an example of phonological allomorph. The allomorphs are derived from each other.

Suppletive allomorphs are different phonologically. The forms are not derived from each other.

A good example of suppletion in English is in the marking of tense on irregular verbs; the forms of the present verb and the past are different. For example buy-bought, go-went, run-ran.

5. Basic Morpheme

The basic morpheme is the abstract unit from where the other variants are derived.

It is the morpheme that occurs at the underlying level; it is also identified as one of the alternants.

The basic morpheme is the morpheme that has the widest environment of occurrence. It has the widest distribution compared to other forms. It is the morpheme that occurs in other environments while the variants occur in predictable environments.

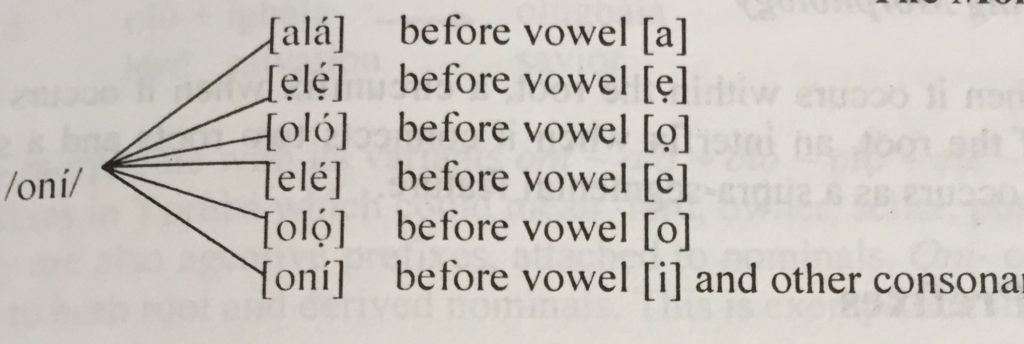

The basic morpheme does not change. The morpheme oní- in the examples discussed above is the basic morpheme as it occurs in other environments while the variants occur in predictable environments. This is shown in (5).

5.

[alá] before vowel [a]

[ẹlẹ́] before vowel [ẹ]

[oló] before vowel [ọ]

/oní/[elé] before vowel [e]

[olọ́] before vowel [o]

[oní] before vowel [i] and other consonants

We can see the morpheme taking different forms depending on the initial vowel of the stem. It however remains the same when it occurs before vowel [i] and consonants.

This means that it is the morph with the highest position of occurrence; therefore, it is the basic morpheme.

Exercises

1. With ample illustrations, classify the morpheme.

2. What is a morph? Describe the difference between the morph and morpheme.

3. Distinguish between a morpheme and an allomorph.

4. Distinguish between a morph and an allomorph.

5. Describe free and bound morphemes.

6. What do you understand by basic morpheme?

NB

a. We will examine roots, stems and bases in the next class.

b Excerpts are taken from Arokoyo (2017).

References

Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth. (2017). Unlocking morphology. Ilorin: Chridamel Publishing House.

Haspelmath, Martins and Andrew Sims (2010). Understanding morphology. London: Hodder Education.

One thought on “Morphs and Allomorphs: morpheme realizations”

Comments are closed.