Bolanle Elizabeth Arokoyo

Morphology Lecture Series #VI

Our topic of discussion in today’s lecture is affixes. If you are just joining, endeavour to go through the previous lectures (Roots, Stems and Bases).

What are affixes?

Affixes are bound morphemes that attach to other morphemes to form words.

They only occur as part of another morpheme, attached to the root or stem. They do not occur in isolation.

Affixes are only meaningful when they are attached to free morphemes.

Affixes are either derivational or inflectional; they perform both lexical and grammatical functions.

They are used to derive new words or to inflect existing words for grammatical functions.

Affixes perform lexical functions when they derive new words and grammatical functions when they inflect existing words.

Lexical functions refer to when an affix is attached to a root or stem in the morphological process thereby resulting in the creation of a new word. This new word might still retain its word class.

Grammatical functions of affixes refer to an affix attached to a root or stem to provide additional information about tense, case, gender, number, etc.

Affixes are attached to other morphemes through a process of affixation.

Affixes are classified according to their position relative to the roots and stems.

An affix may occupy the structural position of a prefix when it occurs before the root, a suffix when it occurs after the root, an infix when it occurs within the root, a circumfix when it occurs at both sides of the root, an interfix when it connects two roots and a suprafix when it occurs as a supra-segmental feature.

1. Prefixes

A prefix is an affix that occurs before the root. It is an affix which appears before the root, stem or base to which it is attached.

A prefix precedes the root or stem to which it is most closely associated.

Most human languages attest prefixes. For example in Yorùbá all oral vowels a-, e-, ẹ-, i-, o-, ọ- except [u] function as nominalizing prefixes in Yoruba.

According to Tinuoye (2000 p24) ‘they are used primarily to form concrete nouns denoting the actor or agent’.

These prefixes are attached to either verbs or verb phrases to derive nouns. For example:

1.

a. kú ‘to die’ i-kú ‘death’

b. ṣẹ̀ ‘to sin’ ẹ̀-ṣẹ̀ ‘sin’

c. fẹ́ ‘to love’ ì-fẹ́ ‘love’

d. jà ‘to fight’ ì-jà ‘fight’

e. kọ ‘to teach’ ẹ-kọ́ ‘education’

f. pẹja ‘kill-fish’

a-pẹja ‘fisherman’

The olú- prefix also in Yoruba is attached to nouns. The derived words are also nouns indicating possession, doer or agent or lord. For example:

2.

a. olú + awo olúwo

lord cult. ‘head of a cult’

b. olú + ìfẹ́ olùfẹ́

lord love ‘lover’

c. olú + ìdánwò olùdánwò

lord examination ‘examiner’

d. olù + ìgbàlà olùgbàlà

lord salvation savior

The oní- morpheme with its variants oní ~ alá ~ oló ~ ọlọ́ ~ elé ~ ẹlẹ́ are also prefixes in Yorùbá which could mean ‘lord, owner, seller, possessor’ etc. They are also agentive prefixes, attached to nominals. Oni- could be attached to both root and derived nominals. This is exemplified in (3):

3.

a. oní + ilé onílé

owner house ‘landlord’

b. oní + ìlù onílù

owner drum ‘drummer’

c. oní + garawa onígarawa

owner tin ‘tin seller’

d. oní + kpákó oníkpákó

owner wood ‘wood seller’

e. oní + epo elepo

owner oil ‘oil seller’

f. oní + awo aláwo

owner cult ‘witch doctor’

g. oní + omi olómi

owner water ‘seller of water’

h. oní + ọmọ ọlọ́mọ

owner child ‘owner of child’

i. oní + ẹ̀sẹ̀ ẹlẹ́sẹ̀

owner sin ‘sinner’

The processes involved in the derivation of the variants have been discussed under Morphs and Allomorphs.

Another prefix in Yorùbá is àì-. It is a prefix attached to verbs, verb phrases and adjectives to derive nouns and adjectives.

The aim is to negativise. Bamgbose (1990, p. 106) describes it as negation of abstract nominals. The derived word is either a noun or an adjective.

4.

a. àì + mọ àìmọ

NEG know ignorance

b. àì + ní àìní

NEG have ‘lack’

c. àì + lọ ailọ

NEG go ‘not going’

d. àì + da. àìda

NEG be good ‘evil’

e. àì + sùn. àìsùn

NEG to sleep ‘vigil’

f. àì + lópin àìlópin

NEG have end ‘eternal’

g. àì + díbàjẹ́ àìdíbàjẹ́

NEG corrupted ‘incorruptible’

h. ài + lówó àìlówó

NEG be wealthy ‘poverty’

The prefix ai- is attached to verbs and adjectives in examples (4a-e) and attached to verb phrases in examples (4f-h) respectively.

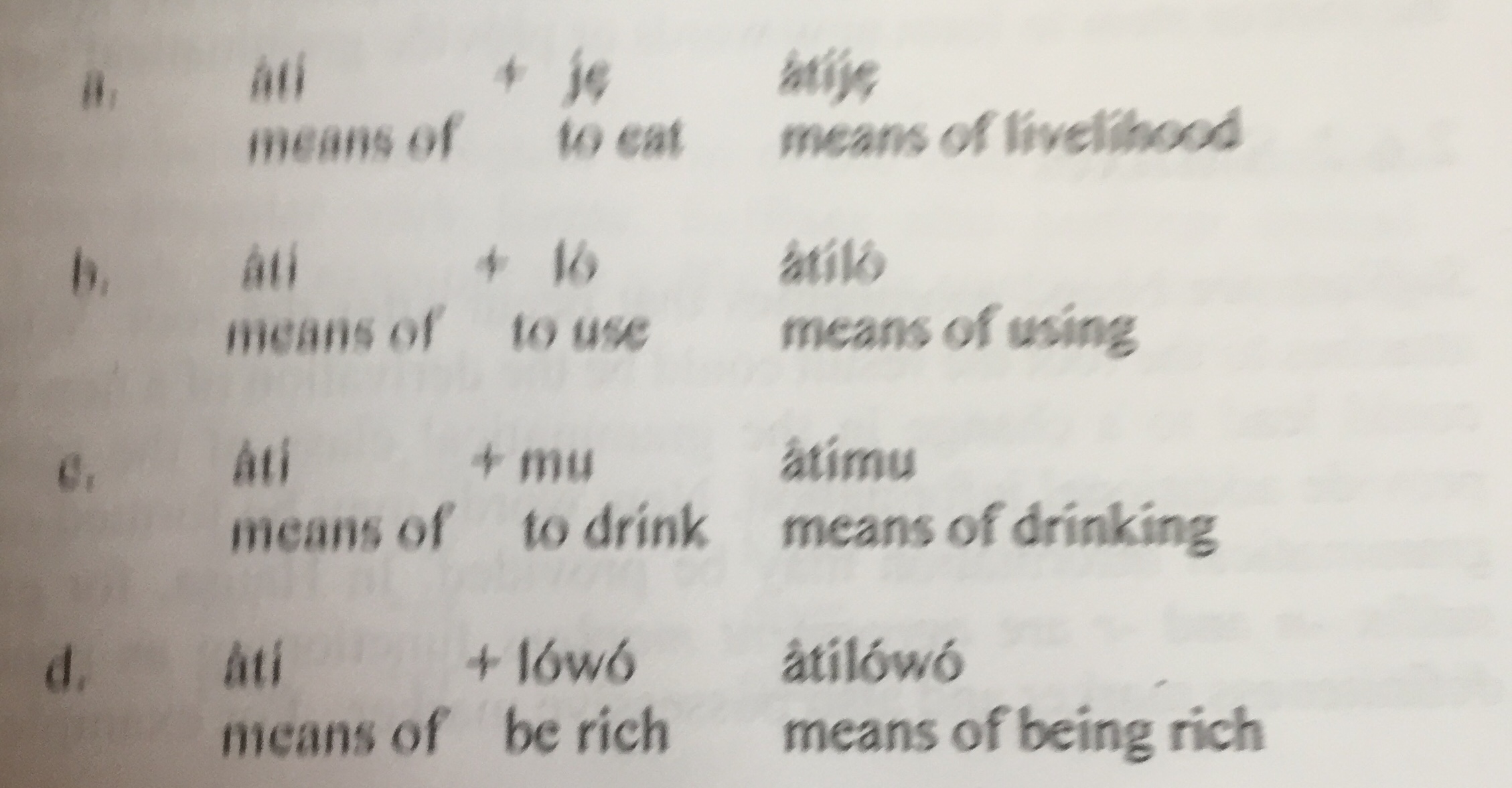

Another prefix in Yorùbá is àti- which is also attached to verbs and verb phrases to derive gerundive nouns.

5.

All these prefixes in Yorùbá perform lexical functions as they derive new words. In Igala, the prefix am- performs the function of plural marking. For example:

6.

a. ónú ‘king’ àm-ónú ‘kings’

b. íye ‘mother’ àm-íye ‘mothers’

c. àtá ‘father’ àm-àtá ‘fathers’

d. ọ́nẹ̀ ‘person’ àm- ọ́nẹ̀ ‘persons’

The plural morpheme in Isthmus Zapotec, spoken in Mexico is the prefix ka-. The following data is taken from Fromkin, Rodman and Hyams (2011, p.44).

7.

a. zigi. ‘chin’

kazigi ‘chins’

b. zike ‘shoulder’

kazike ‘shoulders’

c. diaga. ‘ear’

kadiaga ‘ears’

From the discussion above, we see that prefixes perform both lexical and grammatical functions depending on the morphology of the language.

Prefixation is the process by which bound morphemes are attached before the root or stem to form new words or provide grammatical information.

2.Suffixes

Suffixes are bound morphemes that occur after the root. When a suffix attaches to the root the result could be the derivation of a new word which could lead to a change in the grammatical class of the root or just to provide additional information.

New words may be formed or additional grammatical information may be provided. In Hausa, for example, the suffix -n and -r are agreement markers functioning as gender marker, definiteness marker and also possessive marker. For example:

8.

a. úwá + -r úwár

mother the mother

b. kásá + -r kásár

city the city

c. úbá + n úbán

father the father

d. gídá + n gídán

house the house

In English, the suffix –ed when attached to verbs marks the past tense. The following data illustrate this:

9.

a. kill + ed killed

b. like + -ed liked

c. walk + -ed walked

d. cook + -ed cooked

e. sleep + -ed slept

f. catch + -ed caught

g. buy + -ed bought

h. hit + -ed hit

Examples (9a-e) indicate the regular form of the verb while examples (9e-h) indicate irregular verb forms.

Suffixes also perform lexical functions in English. For example the suffix –er is attached to verbs to derive nouns.

10.

a. sing +er singer

b. kill +er killer

c. do +er doer

d. play +er player

There are two –er suffixes in English. The second suffix is attached to adjectives to derive the comparative form, in which case, it is performing a grammatical function. For example:

11.

a. big +-er bigger

b. small +-er smaller

c. large +-er larger

d. long +-er longer

Suffixation is the process by which bound morphemes are attached after or at the end of the root or stem to form new words or provide grammatical information.

3.Infixes

An infix occurs within a morpheme. An infix would break a morpheme in two and be attached between the broken morpheme; it is incorporated into the root.

For a bound morpheme to qualify as an infix, it must have form and must be incorporated in the root. Infixes are not as common as the prefix or suffix.

Examples of infixes from Tagalog (an Austronesian language), Oaxaca Chontal (spoken in Mexico), Katu (spoken in Vietnam and Bontoc (spoken in the Philippines) show the infixes –in-, -ɬ-, -an- and –um- inserted within roots in the four languages.

Tagalog

12.

a. ibigay ‘give’

ib-in-igay ‘gave’

b. ipaglaba ‘wash(for)’

ip-in-aglaba ‘washed for’

c. ipambili ‘buy(with)’

ip-in-ambili ‘bought(with)’

Oaxaca

13.

a. tsetse ‘squirrel’

tse-ɫ-tse ‘squirrels’

b. tuwa ‘foreigner’

tu-ϯ-wa ‘foreigners’

c. łipo ‘possum’

łi-ł-po ‘possums’

Merrifield et. al. (2003)

Katu

14.

a. gap ‘to cut’ g-an-ap ‘scissors

b. juut ‘to rub’ j-an-uut ‘cloth’

c. piih ‘to sweep’

p-an-iih ‘broom’

Merrifield et. al. (2003)

Bontoc

15.

Nouns/Adjectives Verbs

a. fikas ‘strong’

f-um-ikas ‘to be strong’

b. kilad ‘red’

k-um-ilad ‘to be red’

c. fusul ‘enemy’

f-um-usul ‘to be enemy’

In three of these languages, the infixes are inserted after the initial consonants of the roots (12, 14, & 15) while in Oaxaca (13), it is inserted after the first syllable.

In Tagalog, the infix is a past tense marker, it is a plural marker in Oaxaca, in Katu it nominalizes while in Bontoc, it derives verbs from nouns and adjectives.

Tagalog sometimes forms the basic voice with the infix –um- as shown in (16).

Tagalog

16. Root Basic form with voice

a. langoy l-um-angoy ‘swim’

b. wagayway w-um-agayway ‘wave’

Infixation is the process by which an affix is incorporated into roots or stems to derive new words or provide grammatical information.

4.Interfix

Interfixes are affixes that occur between two root morphemes.

The root morphemes may be identical or non-identical. The interfix acts more like a linking affix joining two roots together. English does not have interfixes but it is attested in Yorùbá. For example:

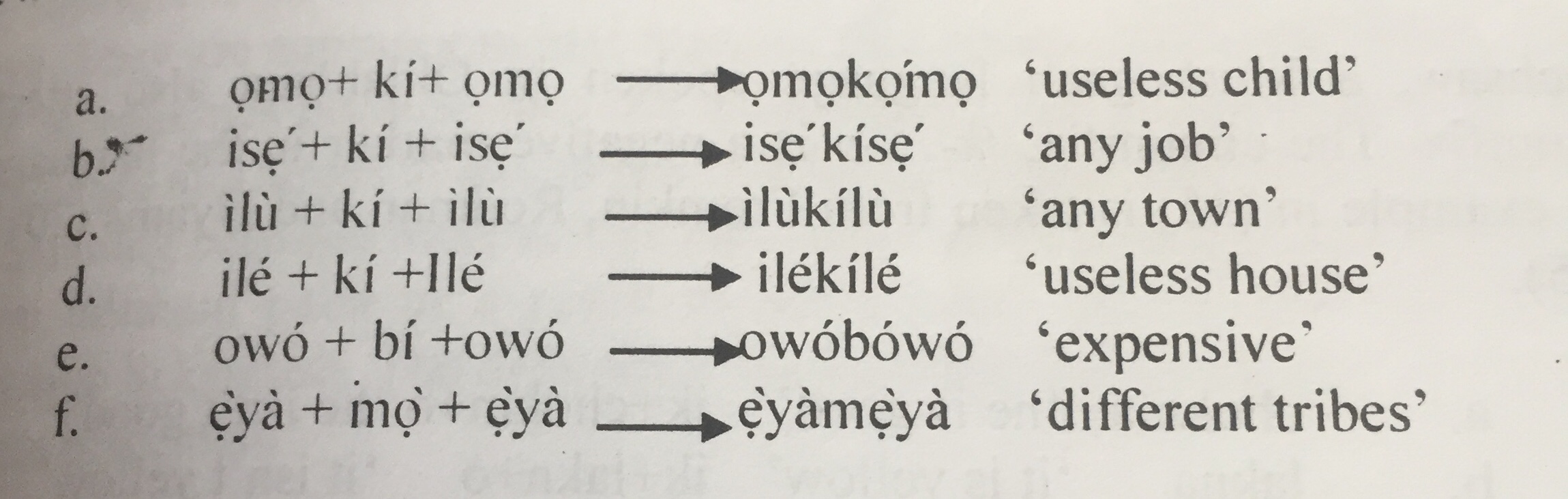

17.

The morphemes –kí-, -bí- and mọ̀ are the interfixes bringing the two identical roots together. Let us also consider these examples from Igbo.

18.

a. ógó-l-ógó ‘length’

b. áká-m-ányá ‘bravado’

c. érí-m-érí ‘meal’

d. ékwù-r-ékwù ‘talkativeness’

e. ụ̀wà-t- ụ̀wà ‘eternity’

These examples illustrate interfixation in Igbo language leading to the derivation of nouns.

5. Circumfix

A circumfix is an affix that surrounds the root. The circumfix has two parts, the first part occurs before the root while the second part occurs after the root.

It looks like both a prefix and a suffix expressing the same meaning.

It is seen as a discontinuous morpheme. German and Chicksaw are circumfixing languages.

The German circumfix ge-…-en and ge-….-t are good examples. This is illustrated in (19).

19.

a. fahr ‘drive’

ge-fahr-en ‘driven’

b. finden ‘find’

ge-fund-en ‘found’

c. singen ‘sing’

ge-sung-en ‘sung’

d. lieb ‘love’

ge-lieb-t ‘loved’

Chichsaw, a Muskogean language spoken in Oklahoma also attests circumfix.

The circumfix, ik-…-o is a negative marker in the language. The example in (20) is taken from Fromkin, Rodman and Hyams (2011, p. 45).

20.

a. chokma ‘he is good’

ik+chokm+o ‘he isn’t good’

b. lakna ‘it is yellow’

ik+lakn+o ‘it isn’t yellow’

c. palli ‘it is hot’

ik-pall+o ‘it isn’t hot’

d. tiwwi ‘he opens (it)’

ik+tiww+o ‘he doesn’t open (it)’

In the Chichsaw examples, before the second part of the circumfix is added, the final vowel is deleted.

In Urhobo, the gerundive and infinitive verb is derived through the use of a circumfix as exemplified in (21).

21. Verb Gerund

a. mi ‘wring’

èmió ‘to wring/ wringing’

b. bi ‘be black’

èbió ‘to be black/ blackening’

c. ku ‘pour’

èkuó ‘to pour/ pouring’

d. mu ‘carry’

èmuó ‘to carry/ carrying’

e. re ‘eat’

ẹ̀riọ́ ‘to eat/ eating’

(Aziza 2010, p. 300-1)

The circumfix, which is allomorphic, conditioned by ATR features, is è—ó and ẹ̀—ọ́. The allomorphic variant è—ó is for +ATR stem while ẹ̀—ọ́ is for –ATR stems.

Circumfixation is, in essence, a situation where both the prefix and suffix are simultaneously employed to express one meaning.

6.Suprafix

A Suprafix is an affix which is marked over the segments that form the root.

They are suprasegmental features like tones, stress, and pitch. They are morphemes because they are meaningful.

For example, tone in tone languages and stress in languages that mark stress bring about differences in meaning between morphemes that have the same segments.

Words can form minimal pairs as a result of suprafixes. Stress performs lexical function in English.

The difference between the following sets of words is stress placement:

22. Nouns Verbs

‘present pre‘sent

‘export ex‘port

‘insult in‘sult

‘convert con‘vert

‘permit per‘mit

Stress on the initial syllable indicates nouns while stress placed on the second syllable derives verbs.

Tones can perform both lexical and grammatical functions. Most African languages are tone languages.

Tones perform lexical function in Nupe, spoken in Nigeria. Consider the following examples in (23):

Nupe

23.

a. bà ‘to count’

bá ‘to be sour’

ba ‘to cut’

b. ebá ‘husband’

ebà ‘place’

eba ‘penis’

c. edú ‘kind of fish’

èdu ‘kind of yam’

èdù ‘Niger river’

edù ‘deer’

edu ‘thigh’

Tones also perform lexical functions in Yoruba as exemplified in (24 & 25) below.

24.

a. igbá ‘calabash’

b. igba ‘two hundred’

c. ìgbà ‘time’

d. ìgbá ‘garden egg’

e. igbà ‘season’

25.

a. ọkọ ‘husband

b. ọkọ̀ ‘car’

c. ọkọ́ ‘hoe’

The morphemes in (24) and (25) above have the same segments; the only difference is the tonal distribution that has brought about differences in meaning.

Looking at the segments and meaning of the words, we can see that the basic difference is in tone variation.

Note that vowels without diacritics in tone languages are marked as mid tones. In Eggon, plurality is marked by changes in the tones of the root word as shown in the examples in (26) below:

26.

Singular Plural Gloss

àklá aklá ‘monkey(s)’

ènú enú ‘fowl(s)’

ìbĩ ibĩ ‘goat(s)’

In the examples, the vowels at word initial positions of the singular nouns carry the low tone while to mark plurality, the low tone changes to mid tone.

Tones also serve grammatical function in Tiv. The imperative is formed with a high tone on the final syllable.

Consider the following examples taken from Haspelmath and Sims (2010, p. 65).

27. Root Imperative Gloss

kimbi kìmbí pay

de dé leave

gba gbá fall

vá vá come

In the formation of imperatives in the language, the high tone is placed on the final syllable.

In Ukaan, spoken in Nigeria, tone makes a distinction between present continuous and the past tense. Consider the examples from Abiodun (2010, p. 55).

28.

a. dzẹ́ wag ‘I am coming.’

b. dzẹ́ wàg ‘I came.’

c. dzẹ́ fẹgẹ èkèrè

‘I am breaking a pot.’

d. dzẹ́ fẹ́gẹ̀ èkèrè ‘I broke a pot.’

Exercises

1. With suitable examples, describe affixes.

2. Be creative! What are the possible forms you can come up with using affixes like un-, in-, dis-, il-, -s, -ren, -ed, on these words. Can you explain why the derived or inflected forms sound the way they do?

possible ox catch hit obvious

regular wife chief go show

legal descript

3. Examine the morphological functions of tones in human language.

4. Identify the morphological constituents and describe their meanings in the following Hyderabadi Telugu (India) data.

pilla ‘child’

pillalu ‘children’

puwu ‘flower’

puwulu ‘flowers’

ʧiima ‘ant’

ʧiimalu ‘ants’

doma ‘mosquito’

domalu ‘mosquitoes’

godugu ‘elephant’

godugulu ‘elephants’

ʧiire ‘sari’

ʧiirelu ‘saris’

annagaaru ‘elder brother’ annagaarulu ‘elder brothers’

Merrifield et al. 2003

NB

a. We will briefly examine Complex Derivations and Zero Morpheme in the next class.

b. Leave your comments and questions on the site.

b Excerpts are taken from Arokoyo (2017).

References

Abiodun, Mike. (2010). Phonology. In Yusuf, Ore (ed.). Basic linguistics for Nigerian languages. Ijebu-Ode: Shebiotimo Publications. 38-65.

Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth. (2017). Unlocking morphology. Ilorin: Chridamel Publishing House.

Aziza, Rose O. (2010). Urhobo phonology. In Yusuf, Ore (ed.). Basic Linguistics for Nigerian Languages. Ijebu-Ode: Shebiotimo Publications. 278-294.

Bamgbose, Ayo. (1990). Fonọlọji ati girama Yoruba. Ibadan: University Press Plc.

Fromkin, Victoria, Robert Rodman and Nina Hyams. (2011). An introduction to Language. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Haspelmath, Martins and Andrew Sims (2010). Understanding morphology. London: Hodder Education.

Merrield, R. William, Naish, Constance M., Rensch Calvin R. & Gillian Story. (2003) (7th Edition). Laboratory manual for morphology and syntax. SIL International: Dallas, Texas.

Tinuoye O. Mary. (2001). A contrastive analysis of English and Yoruba morphology. Ijebu-Ode: Shebiotimo Publications.

3 thoughts on “Affixes: Bound Morphemes”

Comments are closed.